Introduction

The popularity of the web has given birth to a new data economy. A. Asensio recognises that the most successful companies on the web are “data-driven and data-focused”. These are the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Google, and Apple [1]. Therefore, as data has become the new gold, this has given rise to several ethical considerations in relation to personal data.

Defining Personal Data

Hummel et al. acknowledge that data creates benefits and potential for agents and stakeholders, but that it also leads to challenges in retaining control over their data. Furthermore, the issue of data sovereignty encompasses a range of agents, including individual consumers, entire societies, and countries. This has ultimately caused conflicting claims to data sovereignty [2].

In the UK, data sovereignty and personal data governance are handled within the confines of the UKGDPR (United Kingdom General Data Protection Regulation). Within the UKGDPR and European GDPR, entities are recognised as:

- Controllers, or joint controllers, as the names suggest, are the people in control of the data.

- Processors, or sub-processors, may perform processing operations on data but do not have overall authority.

- Data subjects are the people whose data is being controlled or processed [3].

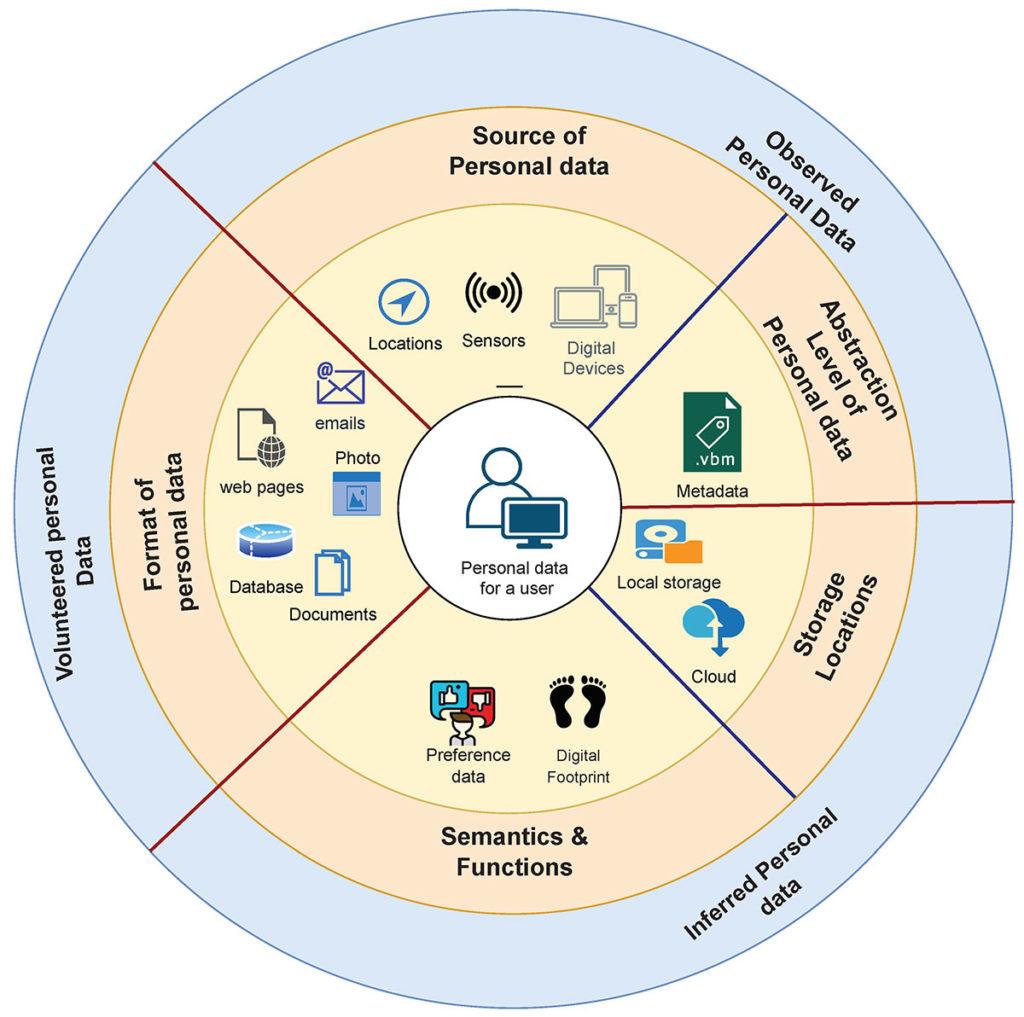

However, it is also important to establish what exactly constitutes personal data. According to K. U. Fallatah et al., personal data can be classified into multiple dimensions, as illustrated in [4, Fig. 1].

Figure 1. Dimensions of Personal Data

[4]

As can be seen, personal data is generated from a variety of sources. However, it is worth noting that in North America, it is common to refer to personally identifiable information (PII), which includes medical, educational, financial, and employment information. All this information, under GDPR, is considered personal data. However, GDPR covers a much wider scope of data [5].

Personal Data Risks

Personal data is often sold for profit or used for surveillance, such as tracking movements and monitoring behaviour [6]. Many people are unaware or simply indifferent to how personal data is used. A private company, Nomidio, carried out an analysis in 2020 and found that “At least 39 different organisations hold personal data on the average UK citizen” and “82% of people are unsure of what personal information companies hold about them” [7]. Another private organisation, ProPrivacy.com, claims to have succeeded in persuading 99 percent of survey respondents into agreeing to ridiculous things within their terms and conditions, e.g., signing over the naming rights of their first-born child and inviting an FBI agent to Christmas dinner [8].

Similar findings have also been reflected in the academic literature. S. Schudy and V. Utikal state that few consumers take the time to read, understand, and make conscious choices about opting out of information sharing [9]. Furthermore, J. H. Beales and T. J. Muris recognise the impracticability of the notice approach to privacy, stating consumers see information sharing as “not worth thinking about” [10].

Paradoxically, a study by Pew Research found that 79% of Americans are concerned about the way their data is being used by companies, and 64% are concerned about the government collecting data on them. D. Lupton and M. Michael stated that “several highly-publicised events and scandals have drawn attention to the use of people’s personal data by other actors and agencies, both legally and illicitly” [11]. One such event is the Cambridge Analytica scandal. The British consulting firm was able to collect data from 87 million Facebook users without their consent, including 320,000 user profiles and their friends’ data [12]. Therefore, awareness and fears due to such events have increased.

Proposed Solution

Ultimately, data protection has become a priority. As a result, many privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) are being developed to assist organisations and individuals with better data protection [13]. One proposed solution is an abstract concept called a personal data store (PDS). There are many types of PDSs with various use cases and implementations. However, the basic concept is to “decouple data from applications” [14] to give users control over their data. H. Janssen et al. state that “PDSs represent a point for user intervention and mediation in digital ecosystems” [15]. H. Janssen et al. go on to describe the potential architectures of PDSs. These could potentially be a physical device designed for the home or, alternatively, software that is stored in the cloud [15].

Tim Berners-Lee’s company, Inrupt, has developed a product they call PODS (Personal Online Data Store). They envision three options for users. Either a physical or cloud-based POD is provided by the PDS supplier, or alternatively, if a user has the technical know-how, they could run their own POD on their own hardware with open-source software [16]. Of course, this would make users responsible for their own security and hardware maintenance, which is beyond the reach of the average user.

Ultimately, the goal of a PDS’s functionality is to:

- Capture and store users’ personal data locally within their own device (either at home or in the cloud), separating personal data from applications.

- The computation of data is to occur locally on the PDS (analytics), with constraints put on managed apps as directed by user preferences. User preferences will be stored with the PDS manifest, and options could be set horizontally across all apps, e.g., by not sharing location data with any app, or specific settings could be applied for individual apps. Ultimately, the idea is to have granular data settings.

- Management and control regarding any transfer of raw data and/or results of analytics

- The ability for users to monitor, manage, and control all the above, with risk ratings applied to apps, much like in the Google Play Store or Apple App Store. As well as the provision for logs, audits, and visualisations to provide users with insight as to exactly how their data is being used.

[4] [15]

Cloud-Based PDSs

If PDSs see mass adoption, it is likely that the average user will choose a PDS that is provided by a supplier. i.e., they will not run their own open-source software because of the technical skill required. Furthermore, cloud services will likely be the more cost-effective option as opposed to physical devices, as there is no manufacturing cost. Therefore, it is likely that cloud-based options will be a popular choice among consumers. W. Li et al. state that cloud subscription models are lucrative business models [17]. However, W. Li et al. go on to say that cloud systems have encountered serious trust and security problems:

- In 2016, Cloudflare experienced a critical bug in its software, which resulted in a privacy data leakage that affected approximately 2 million websites. This included well-known companies such as Uber.

- In 2017, Microsoft experienced a failure in its Azure public cloud storage, which affected many cloud-based businesses for more than 8 hours.

- In 2017, Amazon had a security breach in its AWS cloud service, which resulted in the exposure of the personal information of 200 million US voters.

[17]

It is the author’s view that ultimately, the concern with the cloud-based model is that users data will remain in the hands of a third-party, i.e., a cloud PDS provider. Therefore, users will be at the mercy of their competence, reliability, and integrity. Furthermore, PDS providers will be constrained by the laws in their location, which may require that access to data be given to authoritarian governments. Similarly, criminals may breach the security of the PDS provider’s servers, or the PDS business owners may not act lawfully or in the interests of their customers.

Comparisons can be drawn with the crypto industry. Recent events demonstrated the fragility of coin exchanges, which are essentially cloud-based services that store crypto keys and manage crypto currencies on behalf of customers. Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) and his coin-exchange company, FTX, collapsed. SBF has been charged with alleged illegal political donations and bank fraud, and his customers were left with heavy financial losses [18].

This contrasts with the model that many Bitcoin activists follow, which is to store their crypto keys either on a hardware or software wallet that only they control (this is known as a self-custodial wallet) and that gives no access to third parties. Not even governments could access a self-custodial wallet by demanding organisations give them access, because without the keys, which are secured by the cryptographic 12-phrase password, which only the user knows, it is currently seen as impossible to gain access. This is why there is a common adage in the crypto world that states, “Not your keys, not your coins” [19]. Ultimately, trusting third parties with anything valuable, whether that is data, crypto currency, or anything else, puts individuals at the mercy of third parties.

Physical PDSs

Physical PDSs, of course, will incur extra costs in terms of manufacturing. However, this extra cost could potentially lessen the risk of a centralised server being hacked and putting user data at risk. Though at the same time, it would require that the device be designed securely so that these devices do not become vulnerable to attack, especially when connected to a smart home network [20].

In 2019, the BBC announced that they were working on a prototype called the BBC Box. It was powered by a Raspberry Pi computer and used the Databox personal data management system [21] [22]. It is the author’s view that a physical PDS could be a viable solution, provided that the design is secure. However, a physical device would not negate the risk entirely, and in fact, having a user’s data stored in one place could potentially make the device itself a target.

Benefits and Risks

Ironically, one of the things touted by PDS supporters is that with more trust, users will likely be less resistant to data sharing. i.e., this may lead to the sharing of more useful data. For example, a combination of medical data could be matched with eating patterns, or bank statements could be combined with shopping history to analyse a user’s spending habits or health choices for deeper analytical insights [4] [15]. However, considering the already existing risk to personal data, the author is concerned that encouraging people to create and store even more personal data is potentially counter-productive. Therefore, more research is needed as to the potential risks of encouraging people to store even more personal data that can potentially be accessed online.

However, it is fair to recognise that there are many potential benefits of a PDS for users. including personalised services, granular control over data sharing and processing, better informed consent guided by risk ratings, real-time monitoring with visualisations, prevention of unauthorised access by app developers, incentives for app developers to become more privacy-oriented, and opportunities for users to monetise their data [4] [15]. However, these benefits will likely vary depending on the implementation of a particular PDS, and thus, caution should be taken to ensure that PDSs do not inadvertently create more risk for users and their data.

Legal Implications

Due to the variations in PDS implementation and design, the Terms of Service (ToS) will also likely vary. Furthermore, governance and technology are still evolving. Therefore, it is not yet clear how PDSs will affect GDPR and current case law [15].

H. Janssen et al., propose the following potential problems and changes:

- If data processing is carried out by several organisations, it may be more difficult to identify the controller or joint controllers. This conflicts with the initial intention of GDPR, which is to assign responsibility for data handling. Though it is possible that both PDS platforms and app developers will become joint controllers,

- With platforms, users, and developers playing varied roles depending on the specifics of a PDS, this collaboration of entities makes it more difficult to determine the exact role of each entity.

- Currently, data subjects are seen as “passive” in data processing, but as users and data subjects are given more control, this may challenge the GDPR label of data subject.

- Lastly, open-source software has the potential to challenge both the labels of controllers and processors because, due to the nature of PDS technology, technically, a user has the potential to become a data subject, processor, and controller in varying degrees. Yet, it is unlikely that they will be classified as controllers or processors since most home users’ activities would fall under the household exemption. This is where individuals are exempt when data is not being used for commercial interests [15].

As we look to the future of privacy law, it is important to recognise the disconnect between the law as it is written and implemented. The GDPR law in and of itself has been insufficient at protecting people’s privacy. The law alone simply cannot do this, hence why we have seen several proposals for PETs and indeed PDSs. As P. Arora plainly puts it, “The notion of GDPR as a golden and global standard is commendable. However, regulations are meaningless without enforcement. And yet we disproportionately focus on the design of the law and far less on the implementation” [23].

Digital ID

Another risk of PDSs is not the PDS itself, but another technology that is required for the PDS concept to work. That is digital ID, and potentially, and more dangerously, persistent digital ID. Ultimately, for any user to have their personal data assigned to them, they must be identifiable, and for consistency, that ID would need to be persistent.

Traditionally and more broadly, identification has been issued in the form of physical identification by a central authority, such as governments. This includes passports, driving licences, and national insurance numbers. However, globally, there has been a push towards digital ID as part of the United Nations member states adoption of the “Sustainable Development Goals”. This includes a commitment to legal identity for all by 2030 [24]. In the UK, the government has drafted new legislation to make digital IDs more valid [25]. However, not all digital ID is the same, and how digital ID is implemented will have varied consequences.

Up until now, verification online has often been done with phone numbers, email addresses, and usernames. However, these identifiers are issued and controlled by the suppliers, such as phone and email providers, as well as social networks. As a result, these identifiers can be revoked at any time by the issuer, leaving the user without their identification [26]. B. Podgorelec et al. label this model of digital identification and authentication as “isolated” because the user requires different credentials for each service provider [27]. The issue with this model, as J. Sedlmeir et al. recognise, is the dissatisfaction of users with the need to remember multiple passwords [28].

Podgorelec et al. go on to describe the “central identity” model, whereby users will register with an identity provider that will authenticate them to multiple services. However, this makes the central identity provider a “single point of failure” [27]. B. Podgorelec et al. continue with the “Federated Model,” whereby a circle of trust is created with multiple identity providers. This prevents a single point of failure, and users’ information is stored in a more distributed manner. The European eIDAS framework is an example of this and allows EU Member States to enable cross-border authentication [27]. However, all the above models rely on central authorities to store users’ data, which makes them vulnerable to attack.

As a result, many PDS creators opt for a form of digital ID known as decentralised identifiers (DID). DID is a W3C standard. They are designed to be a verifiable identifier and not require a centralised authority. It is said by the W3C that DIDs will “enable both individuals and organizations to take greater control of their online information and relationships while also providing greater security and privacy” [29]. A DID should be decentralised, persistent, cryptographically verifiable, and resolvable [30]. There are different potential implementation methods for DIDs. These include:

- Distributed ledgers such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, or a custom-built ledger.

- DID documents stored on a specialised website [31].

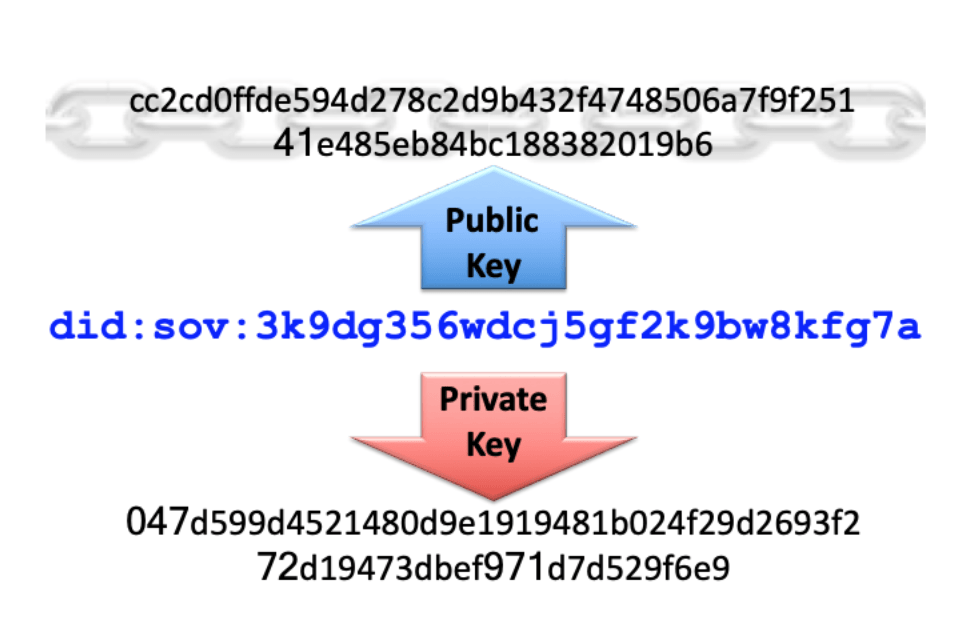

Essentially, the identifier of a DID is simply a new type of Uniform Resource Identifier (URI), as can be seen in [31, Fig. 2]. The `did` section is the type of URI, much like the http in today’s Uniform Resource Locators (URLs). The `sov` is the type of DID, whether it is stored on the bitcoin network or another. Then the final part of the URI is the individual identifier. Finally, the DID is cryptographically protected by public and private keys.

Figure 2. DID

[32]

Prof. G. Gensler from MIT discusses how digital IDs on the blockchain are basically hash functions, and once stored, they are immutable [33]. Therefore, it works well for persistent ID. However, Prof. G. Gensler raises an important issue as to how the blockchain is an open ledger; therefore, it may not be suitable to store personal information on it [33].

A WebID is another type of digital identifier built into your browser with current web technologies, using Transport Layer Security (TLS) and digital certificates with public and private keys generated by the browser and authenticated by the server. They also use a URI along with linked data. As a result, WebID also does not require a central issuing authority, nor does the user require a password [34].

There are many similarities between DIDs and WebIDs. For instance, both use URIs that resolve to linked data documents, and both are interoperable. However, WebIDs tend to store more PII information, such as name, email, or user profile pictures, which DIDs do not. Furthermore, there are multiple potential implementations of DIDs, including both web and distributed ledgers, whereas, as the name suggests, WebIDs are purely web-based [35]. Ultimately, though, both WebIDs and DIDs are very similar concepts, and both are seen as important technologies for the future of digital authentication within the W3C community; thus, both are W3C standards.

The EU is considering the DID standard as well as other centralised and federated identity models for their EU digital wallet [36] [37]. According to the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), “European citizens should have the possibility to use a digital identity to access key public services by 2030 and to do so across EU borders” [38]. They also propose that EU citizens will be able to “identify and authenticate themselves online (via their European digital identity wallet) without having to resort to commercial providers” [38]. They claim that using commercial providers “raises trust, security, and privacy concerns” [38].

There is much debate as to the implementation and requirements for digital ID. Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, stated, “Every time an App or website asks us to create a new digital identity or to easily log on via a big platform, we have no idea what happens to our data. That is why the Commission will propose a secure European e-identity. One that we trust, and that any citizen can use anywhere in Europe to do anything from paying your taxes to renting a bicycle. A technology where we can control ourselves what data is used and how” [39].

Ivan Bartos, the Czech Deputy Prime Minister for Digitalisation and Minister of Regional Development, has said, “Digital technologies can make our life so easy. I am convinced that a European digital identity wallet is indispensable for our citizens and businesses. We are looking at a massive advancement in how people use their identity and credentials in everyday contact with both public and private entities, and in how they use digital services. All while firmly keeping control over their data” [40].

However, Rob Roos, an MEP and a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists Group, has said, “The EU wants to ram the Digital Identity through. I took the initiative to hold at least a Plenary vote on it. A plan as far-reaching as the Digital Identity merits a debate. But the majority of the MEPs voted to ram it through directly. Shameful & undemocratic” [41] [42].

It is not just the EU that is pushing forward with digital identity and PDSs. Digital ID is seen as a necessary development in a modern technological world. M. Dahan and R. Sudan of the World Bank state that a “lack of personal official identification (ID) prevents people from fully exercising their rights and isolates them socially and economically” [43].

In the UK, according to Computerweekly.com, the British government has also looked to Tim Berners-Lee and his company Inrupt to help with their digital identity plan [44] [45]. Furthermore, it has been reported that Natwest Bank, BBC, NHS, and the government of the Belgian region of Flanders are running pilot schemes using Berners-Lee’s Solid Servers [46] [47] [48].

Tony Blair, the ex-British prime minister who led the UK into war with Iraq, a war that Kofi Annan The United Nations Secretary-General called it “an illegal act that contravened the UN charter” [49], and a war that led to a “massive death toll” [50] supports digital IDs. Blair has expressed his support for a medical database for citizens vaccine status at an address at the World Economic Forum [51] and joined forces with William Hague in a BBC Radio 4 interview, claiming that digital ID should be “compulsory” for everyone [52].

However, Silkie Carlo, director of the campaign group Big Brother Watch, has responded by saying that the “sprawling digital identity system” promoted by Blair and Hague “would be one of the biggest assaults on privacy ever seen” [52]. Conversely, the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change has been promoting digital ID for many years and published an article during COVID lockdowns stating, “The careful application of technology offers a way out, at a price: dramatically increased surveillance” [53] in an article titled “Everyone Needs to Give Up a Little Privacy to Help Defeat Coronavirus” [53].

Despite the push towards digital IDs by some politicians and wealthy organisations [54] and, of course, the convenience and practicality of the technology, there are, however, serious concerns. J. Schroers reasons that “the introduction of a unique and persistent identifier could be understandable from a practical point of view but cannot be accepted due to its risks” [55].

J. Schroers highlights these risks by stating that “all information about a person can be connected and a full profile can be made without the knowledge of the person, which can be used to their disadvantage” [55]. Furthermore, “all the information about a person can be connected throughout one’s whole life, even if, for example, somebody changed their name or moved to another country for good reasons”. Lastly, persistent identifiers “can facilitate unlawful data exchange, aggregation and profiling” [55].

Furthermore, T. Lohninger of the digital rights umbrella group said during an EU eIDAS reform hearing that persistent identifiers are “illegal in Austria and the Netherlands and unconstitutional in Germany” and that “proper safeguards are missing” [56].

Summary

The implications of PDS and digital ID are far-reaching but may be good or bad. This will depend entirely on the technical implementation. The result will either be decentralised, giving users more control, or centralised, giving governments and tech companies more control. However, these technologies are still being developed and evolving without mass adoption. As a result, the future of data and identity is still unknown.

- The Future of Personal Data and Digital ID - June 30, 2023

- Mobile Apps and Smartphone Technology: Challenges and Opportunities - December 17, 2022

- AI Cognitive Computing: An In-Depth Look At IBM Watson - August 15, 2022